Psychology Behind: Everything Everywhere All At Once

Exploring intergenerational conflict and trauma through film.

Exploring intergenerational conflict and trauma through film.

We inherit many things from our parents. Some get their mother's eye color, others receive their father's mannerisms. Unfortunately, in some cases, children can inherit their parents' trauma. They are unintentionally burdened with silent wounds left by struggles with loss, sacrifice, and unfulfilled dreams.

For immigrant parents, trauma often comes wrapped in hardship from adapting to a new world: the pain of leaving home, the weight of financial insecurity, language barriers, and the pressure to succeed against all odds. That trauma doesn't just sit in memories or behaviors; it actively shapes how love is given and received.

For many children of immigrants, especially those raised under the weight of unspoken disappointment and emotional restraint, this love can feel like trying to breathe through a wet cloth. It becomes something heavy and unattainable, leaving the heart gasping for air and struggling to find space to just be.

To be clear, in these families, love is not absent. It's just expressed differently, arriving in various forms: a plate of freshly cut fruit, relentless hard work, or the absence of praise. And often, it comes cloaked in criticism: a passing comment about weight or a disapproving glance at a haircut. These are not meant as judgment, but as an expression of care. The intention is love, yet the delivery is a quiet injury.

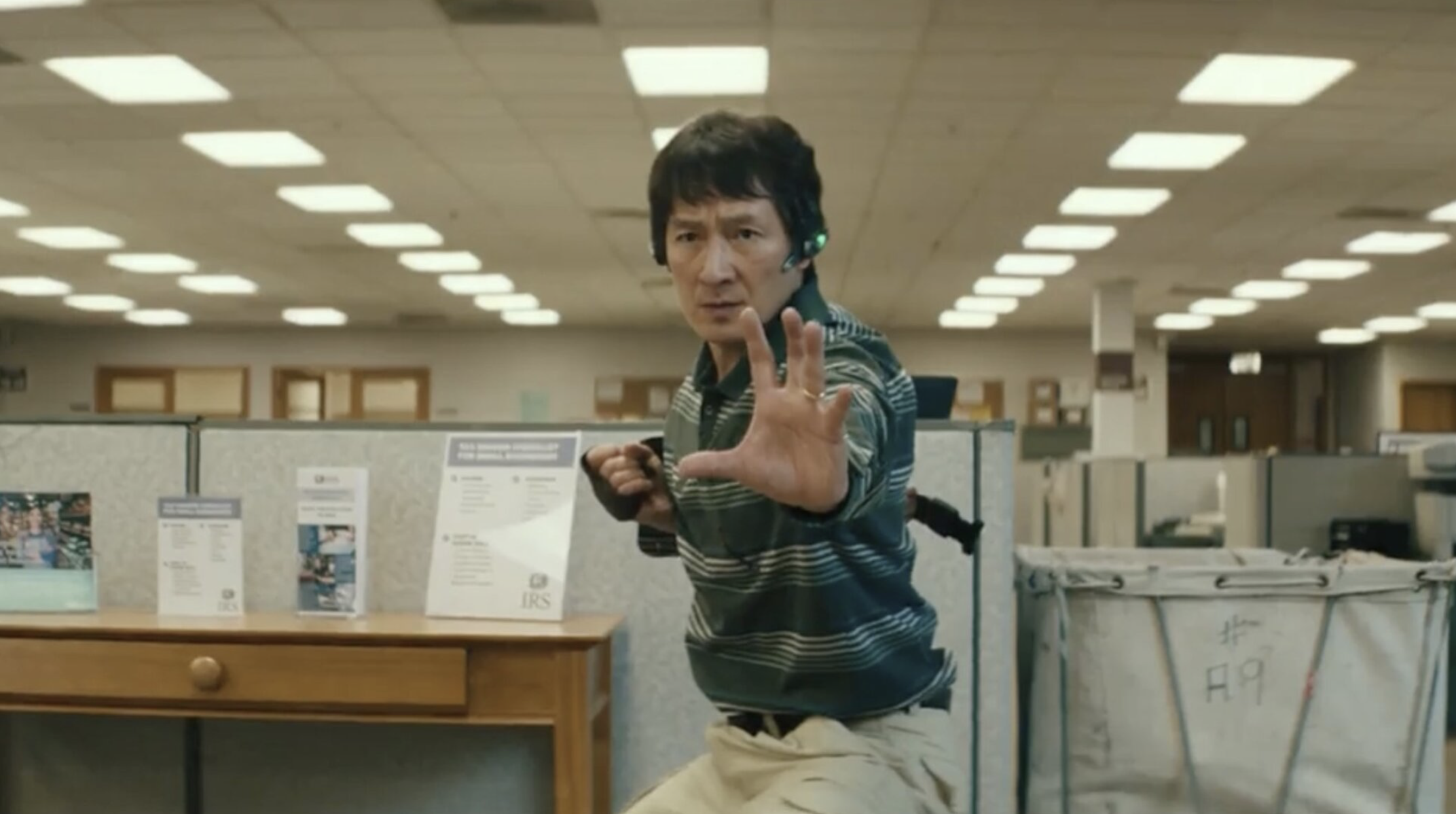

"Everything Everywhere All At Once," directed by Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, follows the chaotic, kaleidoscopic journey of Evelyn Wang, a middle-aged Chinese-American immigrant who is drowning in a mountain of duties. She's trying to run a struggling laundromat, juggle a failing marriage, care for her disapproving father and survive an IRS audit—all while barely holding her family together.

At the heart of the film is Evelyn's strained relationship with her daughter, Joy Wang. Their interactions are tense—punctuated by awkward silences, clipped remarks, and an emotional gulf widened by years of miscommunication. Joy longs for acceptance for her queerness, independence, and voice, while Evelyn, shaped by her own father's disapproval and a lifetime of survival, struggles to express love without judgment or control.

But just as Evelyn is about to crumble under the weight of her ordinary life, the film takes a surreal turn and explodes into something strange yet deeply familiar to anyone who's ever questioned the weight of their choices. She's suddenly pulled into a multiverse: an endless network of realities where every choice she's ever made has splintered off into a parallel version of herself.

In one universe, she's a kung-fu master and movie star. In another, a hibachi chef. In yet another, she has hot dogs for fingers. All the while, she's told that only she can stop a cosmic threat: Jobu Tupaki, a jaded villain who is destroying the multiverse.

"There is a great evil that has taken root in my world and has begun spreading its chaos throughout the many verses. I have spent years searching for the one who might be able to match this great evil with an even greater good and bring back balance. All those years of searching have brought me here…" — Waymond Wang

And Jobu Tupaki? She turns out to be none other than Joy. Or a version of her, cracked open by pain, pressure, and hopelessness. This revelation becomes the emotional core of the film. Evelyn isn't merely fighting to save the universe. She's fighting to save her daughter from falling away into despair from believing that nothing matters.

Two key psychological concepts, often deriving from familial tension, are intergenerational trauma and intergenerational conflict. While they are closely linked, they function in different ways.

Intergenerational trauma refers to the transmission of trauma from one generation to the next. This doesn't always result from dramatic events. Although war, displacement, or systemic oppression are common sources, trauma can also stem from ongoing emotional neglect, rigid expectations, or survival-based parenting.

When left unacknowledged, these experiences can shape everyday behaviors, influencing how love is expressed, how safety is defined, and how relationships are navigated. Children don't just witness their parents' struggles; they internalize them, adapt to them, and often mirror them in their own lives.

This idea of trauma being passed down through emotions and behavior echoes the work of Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, an associate professor and mental health expert who developed the concept of historical trauma. Originally focused on Native American communities, her theory shows how collective trauma from events like colonization and systemic oppression can leave lasting emotional wounds that ripple through generations.

In immigrant families, similar cycles emerge through displacement, sacrifice, and cultural survival. These experiences often go unspoken but appear in parenting styles, emotional restraint, or the pressure to succeed. Brave Heart's work highlights that trauma is not always dramatic or visible; it can be inherited in silence, fear, or the inability to express love openly.

This trauma is rarely passed on directly. Instead, it manifests through patterns like emotional avoidance, perfectionism, chronic guilt, or hyper-independence. A parent who never felt safe might raise a child who fears vulnerability. A parent who never felt good enough might unintentionally push their child toward impossible standards.

Intergenerational conflict, on the other hand, emerges when generational values, worldviews, or emotional needs come into tension. This is especially common in families shaped by cultural shifts or migration. Children may grow up in a social world that looks very different from their parents'—one with new norms, freedoms, and expectations.

What one generation sees as discipline, the next might see as control. What one sees as strength, the other might see as emotional distance.

This entanglement can also be shaped by parenting styles. Developmental psychologist Diana Baumrind identified authoritarian parenting as one of the main approaches to childrearing, characterized by strict rules, high expectations, and limited emotional responsiveness. In families where survival, cultural discipline, or reputation takes precedence, this style is often adopted as a way to instill resilience or control.

However, while well-intentioned at times, authoritarian parenting can contribute to emotional suppression and widen the disconnect between generations.

This kind of conflict isn't just about disobedience; it reflects deeper misalignments between what each generation needs, hopes for, and fears. Parents may expect loyalty or gratitude, while children may be looking for emotional validation or autonomy. In the end, both feel hurt or misunderstood, despite caring deeply for each other.

In Everything Everywhere All At Once, intergenerational trauma is not just a backdrop. It's the emotional engine driving the multiversal chaos. Beneath the absurdist humor, googly eyes, and kung fu battles lies a deeply intimate story about a mother and daughter caught in the long shadow of inherited pain.

Evelyn Wang is not simply overwhelmed by her present. She is burdened by the weight of her past and all the unspoken expectations she inherited. As a Chinese immigrant who left her homeland to build a new life in America, Evelyn carries the trauma of displacement, cultural alienation, and suppressed ambition.

Her life has become a checklist of survival: running a laundromat, caring for a demanding father, raising a daughter, and trying to be a good wife—all while never quite feeling like enough.

That sense of "never enough" is the scar tissue of her own upbringing. Her father, Gong Gong, disapproved of her decision to elope with her husband, Waymond Wang, and emigrate to America. His coldness is not just generational; it is a manifestation of his own rigid survival instincts. The way he withholds warmth mirrors how Evelyn interacts with her daughter, Joy. Without realizing it, Evelyn passes on the same emotional distance she once received.

Joy, raised in a completely different cultural context, represents a new generation grappling with its own identity. She's queer, independent, and deeply aware of her emotional needs but feels unseen by her mother. What Evelyn views as protectiveness or tough love, Joy experiences as rejection.

Evelyn struggles to say "I'm proud of you" or "I see you"; instead, she offers silent judgment or thinly veiled concern. This disconnect is the heart of their conflict. Joy's pain isn't rooted in one moment, but in a lifetime of misattuned love.

This dynamic is brought to life through the character of Jobu Tupaki, Joy's multiversal counterpart. Jobu is not simply a villain: she is the embodiment of what happens when inherited trauma festers unchecked. Her experience of infinite universes has left her fragmented and emotionally untethered. She sees all choices as meaningless, all versions of herself as disconnected. In her nihilism, she mirrors Evelyn's buried fears—that her life, in all its sacrifice and compromise, was for nothing.

But Jobu's despair is not just existential. It is personal. Her chaos is a cry for understanding, a demand that her mother see not just her pain but the systems that created it. Her "everything bagel," a symbol of all-consuming hopelessness, becomes a metaphor for inherited emotional collapse.

When she asks Evelyn to let go, she isn't asking for death—she's asking for release. Release from shame, from performance, and from the exhausting cycle of expectation and disappointment.

Yet, the film doesn't end in despair. It offers a turn: healing. Evelyn learns to stop fighting Joy and to start listening. She confronts her own emotional inheritance and finally chooses a different path. She accepts Joy's queer identity, not with passive tolerance but with active love.

She begins to express care in Joy's language—through words, through softness, and through presence. Most importantly, she resists the belief that her daughter's struggles reflect her own failure. In doing so, Evelyn shows Joy that her life is not meaningless, and neither is theirs together.

"I am no longer willing to do to my daughter what you did to me." — Evelyn

This shift doesn't erase the past; it redefines the future. The cycle of trauma does not break all at once, but with each honest moment, it bends. Evelyn and Joy don't arrive at a perfect relationship—they arrive at something real. And that, in the world of infinite possibilities, might just be everything.

Throughout this film, a truth familiar to many children of immigrants is articulated: when love is filtered through trauma, it becomes conditional, coded, and sometimes cruel. But even so, the film doesn't offer a villain. Evelyn is not a bad mother. She is a woman who was never taught how to love gently, only how to survive.

Intergenerational trauma and conflict are not just abstract psychological terms; they have very real effects on the daily lives and mental health of individuals, especially within immigrant families. The trauma carried by immigrant parents often gets passed down silently to their children. These children grow up bearing the emotional weight of sacrifices and unspoken fears, sometimes without fully understanding the reasons behind their parents' behaviors or expectations.

This inherited trauma can create complex family dynamics where love is expressed through duty and sacrifice rather than open affection. It can lead to emotional distance, anxiety, or struggles with identity as younger generations try to reconcile their parents' cultural values with their own desires and experiences in a new society. These tensions often result in intergenerational conflicts over independence, acceptance, and communication.

Living with unresolved trauma and conflict can contribute to feelings of isolation, confusion, or depression. However, many find healing through therapy, honest conversations, and community support that acknowledge the unique challenges immigrant families face. Recognizing and addressing these patterns is essential to breaking harmful cycles and creating family relationships where love can be openly expressed and freely received.

Everything Everywhere All At Once masterfully explores the messy, complicated feelings that come with intergenerational trauma, especially in immigrant families. Evelyn and Joy's story shows us how unspoken pain and cultural expectations can make love feel confusing or even painful. It's a reminder that healing starts with understanding and honest conversations.

Even if you don't come from an immigrant background, these themes of family, acceptance, and resilience are something we can all relate to. Think about your own family or people you know—how might unspoken history be affecting those relationships?

Family relationships can be complicated, messy, and sometimes painful, but they're also where love often hides. The challenges, misunderstandings, and unspoken expectations don't erase the deep care that underlies these bonds. It takes time, understanding, and patience to navigate the tangled emotions and heal even the deepest wounds.

By learning to see love beyond words and actions, we can begin to bridge the gaps between generations and build stronger connections that embrace both our struggles and our strengths.

If Evelyn and Joy's story made you think about your own family or how love is expressed in your life, we'd love to hear your thoughts on our Instagram, @filmpsychologee!